Only my Strength of Will Remains – Goya Drawings at the Museo Nacional del Prado

The Museo del Prado’s Bicentenary celebrations culminate with an exhibition devoted to the drawings of Francisco de Goya (1746 – 1828). Opening on the exact date of the museum’s 200th Anniversary, the exhibition is the result of a lengthy research project in collaboration with the Fundación Botín to catalogue the artist’s known drawings – half of which are housed at the Prado.

Co-curated by José Manuel Matilla, Chief Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Museo Nacional del Prado, and Manuela Mena, Chief Curator of 18th-century Painting and Goya at the Prado, the exhibition comprises over 300 drawings and surveys Goya’s extensive career. Beginning with his earliest known sketchbooks from his trip to Italy between 1769 and 1771, the exhibition concludes with the drawings completed during his final years in the Bordeaux Sketchbooks [1].

Throughout the exhibition we see Goya’s self-portraits – whether in letters to his childhood friend Martín Zapater or as a tortured genius in The Sleep of Reason – and they provide a fascinating insight into how Goya presented himself both in private and to the wider world.

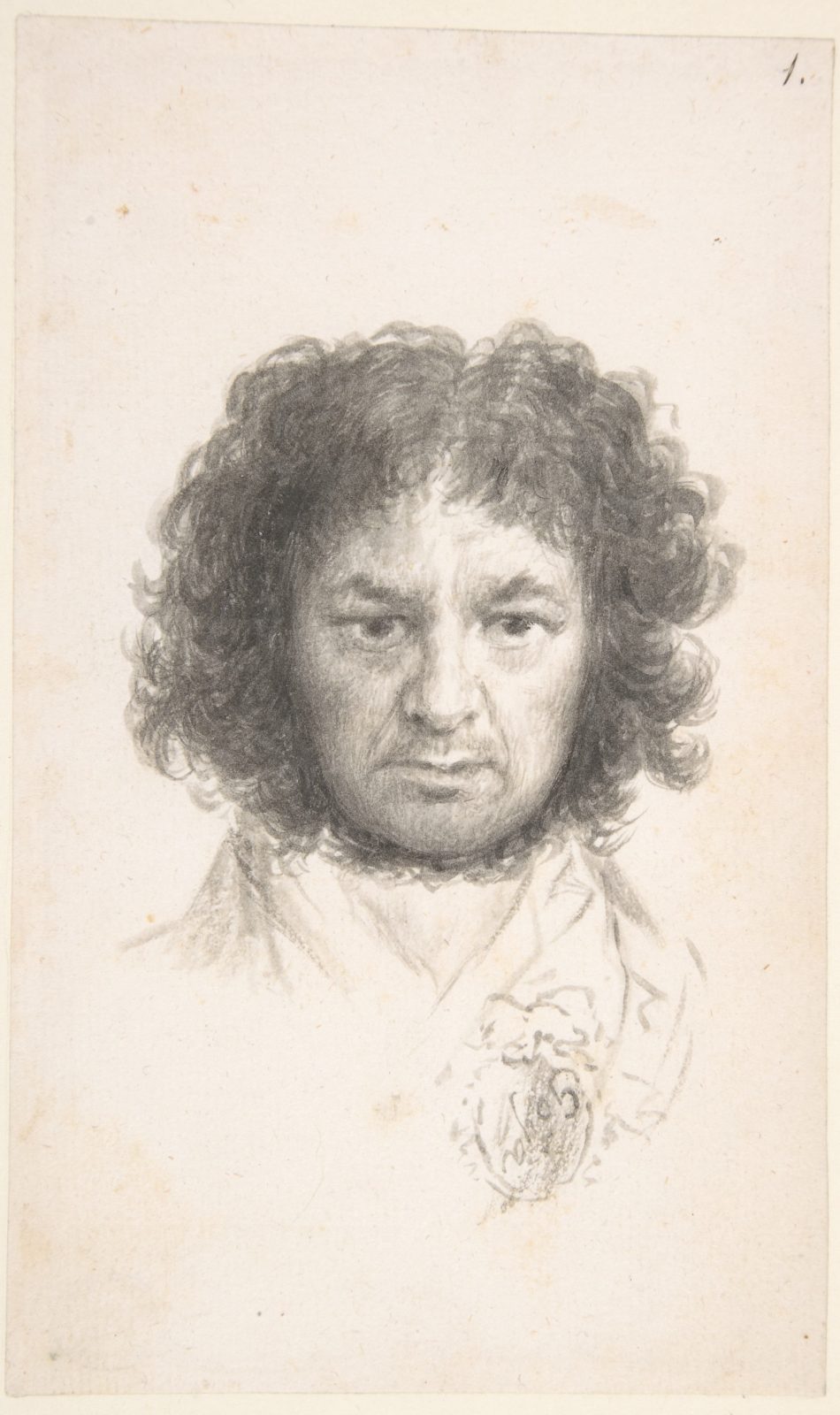

In his Self Portrait of 1796 (Fig. 1, Cat. 1) Goya has positioned himself full-frontal, confidently gazing out at the viewer. Although he has sketchily rendered his attire you can clearly see an imaginary badge of honour with his name inscribed on adorning his chest. Here we see Goya radiating confidence and self-esteem.

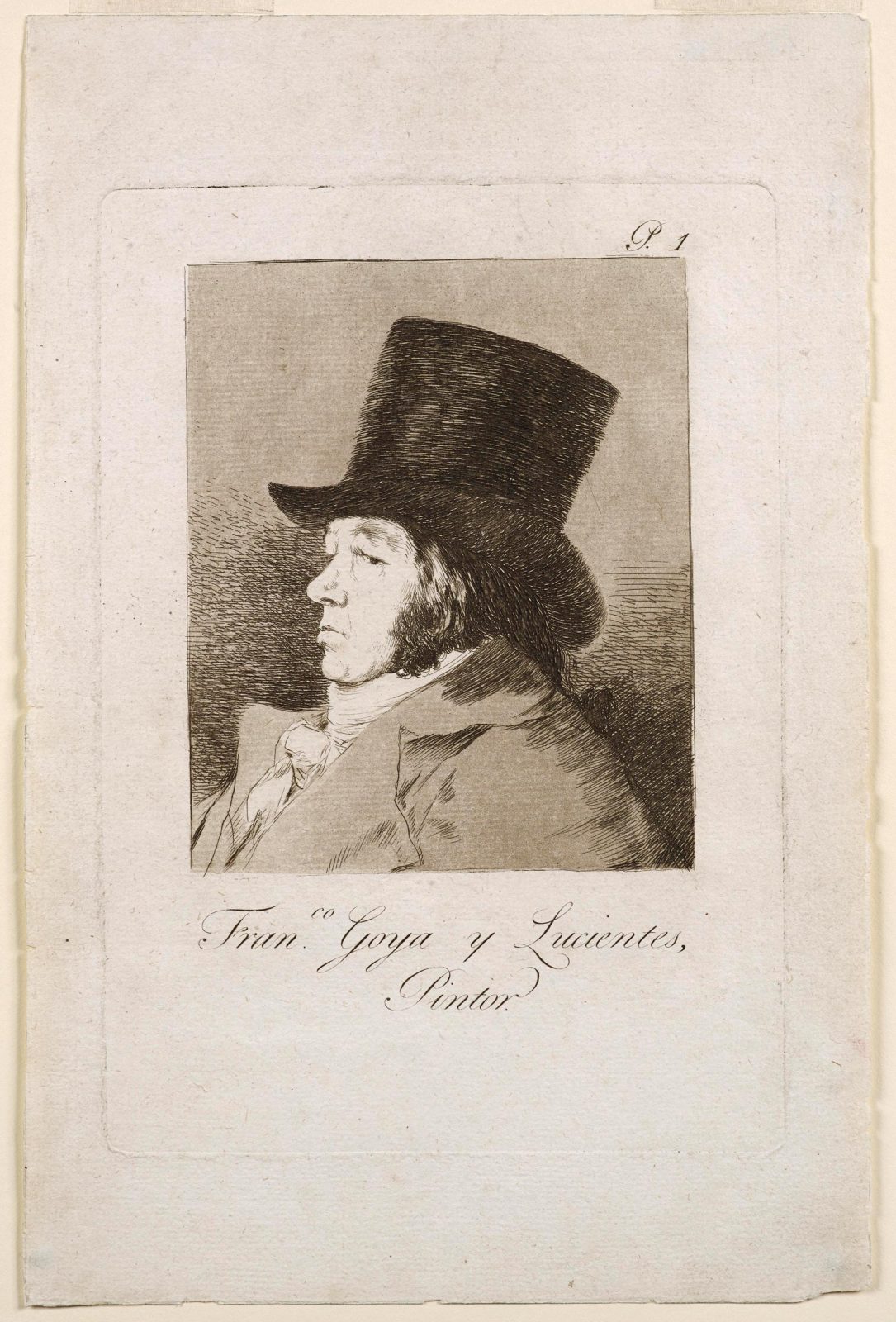

He conveys a similar self-assurance in Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Painter of circa 1797 (Fig. 2, Cat. 182) for the frontispiece of Los Caprichos. Executed in red chalk over black chalk, the composition for the profile portrait is based on that of Scorn from Charles Le Brun’s series of human passions. In the final version for the etching, found in the Katrin Bellinger Collection (Fig. 3), Goya has adjusted his expression so he is no longer staring straight ahead. Instead he looks out at the viewer from the corner of his eye, his lips grimly pursed in a reflection of the weighty content in his “censure of errors and human vices.”

In the second half of his life Goya became obsessed with old age and his later sketchbooks reflect his preoccupation. By 1819 he had lost favour with the royal family and aristocracy. The loss of his hearing after a serious illness and his dwindling circle of friends, many of whom had been persecuted or exiled, had left him feeling increasingly isolated.

The exhibition closes with I Am Still Learning (Fig. 4, Cat. 251), a powerful image which is considered a symbolic self-portrait. Executed at the end of his life it shows an old man hobbled by age, only able to walk with the help of sticks. However, despite the frailty of his body, his face displays a determination to keep progressing and moving forward as declared by Goya himself in his letter to Joaquín María Ferrer in 1825 when he said that “everything fails and only my strength of will remains.”

Goya. Drawings. “Only my Strength of Will Remains” is on at the Museo del Prado until 16 February 2020

Notes:

[1] Matilla, José Manuel and Manuela B. Mena Marqués, Goya. Drawings. “Only my Strength of Will Remains”, exhibition catalogue, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, 2019

Francisco de Goya, Self-portrait, brush and carbon black ink wash on laid paper, 233 x 144 mm, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935, no. 35.103.1

Francisco de Goya, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Painter (preparatory drawing for Capricho I), red chalk over preliminary outline drawing in black chalk, on laid paper, 200 x 143 mm, irca 1797, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971, 1972.118.295

Francisco de Goya, Self-portrait (plate 1 for Los Caprichos), etching and aquatint, 218 x 153 mm, circa 1797-98, Katrin Bellinger Collection

Francisco de Goya, I am Still Learning (Bordeaux Sketchbook [G], sheet 54), black crayon on laid paper, 192 x 145 mm 1824-28 Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, D4151